Last weekend, as smoke blew down from raging wildfires in Canada, officials warned Vermonters to head inside. But Mike Maughan lives in his van, which doesn’t have air conditioning when it isn’t running, and he needed to keep the windows open. The exposure, he said, made his throat burn.

It isn’t the first time Maughan and others who don’t have access to permanent housing have been impacted recently by a weather event that’s likely related to climate change.

On June 1, the day that some 800 people lost eligibility for Vermont’s emergency housing program, the weather was oppressively hot.

As the temperature breached 90 degrees Fahrenheit, residents packed their belongings and left the network of state-funded motel rooms, many of them carrying a collection of bags as they contemplated their next destination. That day, many people told reporters that they had nowhere to go, and that, for the foreseeable future, they planned to live outdoors.

An advocate for the rights of people who are living without permanent shelter, Maughan said there are a number of barriers that keep people who experience homelessness from keeping cool. Some of the publicly listed cooling locations in Vermont aren’t welcoming to everyone.

“It really depends on how you look,” Maughan said.

In the past, when he was living in an unconverted car, he often wore the same clothes several days in a row because he didn’t have anywhere to change. During a recent heat wave, he said, he “didn’t look great, my hair was gross. And I was definitely getting judged by people.” That stigma makes it more challenging to find somewhere to go, he said.

It’s a tradeoff, he said. “You need to go somewhere in public looking like that just to feel more comfortable physically, but now you’re uncomfortable emotionally. So you have to balance the two.”

Lawmakers have extended the pandemic-era motel program to house around 2,200 Vermonters in motel rooms until next April, under certain conditions. But the hundreds who lost their eligibility before the deal became final remain without permanent shelter, and the pre-2020, shorter-term support is the only option for anyone who becomes homeless after July 1.

Vermonters are readily familiar with the cold, and the state has programs that provide options for people during the coldest of winter days. But to keep people safe during the hottest days of summer, the state’s plan is still a patchwork.

Asked at a May press conference how the state was preparing to keep people who don’t have shelter safe during extreme heat events, Jenney Samuelson, the secretary of the Agency of Human Services, said she did not believe the issue was “directly related to housing.”

Not having access to air conditioning is an issue “regardless of whether someone is housed or unhoused,” Samuelson said. “It’s an issue for most Vermonters who are experiencing the stress of that, and I think the Department of Health and others address that, currently, through their cooling shelters and others, and we’ll continue to do that.”

‘More frequently than ever before’

Many Vermonters do not have air conditioning systems in their homes, which can create risks during extreme heat for some, including older people and those with disabilities.

But nationally, people experiencing homelessness are particularly susceptible to heat-related illness due to factors that range from unreliable shelter to higher rates of underlying health conditions.

In Vermont, climate change is causing extreme heat to become more common and dangerous, according to the 2021 Vermont Climate Assessment, which was written by researchers at the University of Vermont and analyzes the impact of climate change on the state.

“In the past, Vermonters generally have known what to expect from each season,” it states. “However, in recent years, Vermont has begun to experience heat waves — prolonged abnormally high temperatures of several days or more — more frequently than ever before.”

Between 2010 and 2021, 70% of the heat waves in Vermont — defined as reaching at least 87 degrees for two days or more — occurred in 2020. By the time the climate assessment was published, in August 2021, two heat waves had already struck the state that year.

The report’s authors predict that, by 2050, Vermont will likely see 15 to 20 extreme heat days each year.

The assessment chronicles an increase in heat-related visits to Vermont emergency departments since 2003, which is expected to rise, along with more instances of heat stroke and dehydration.

In particular, Vermonters who “are more exposed to hot conditions, those who are older or more sensitive to heat, and those who have limited resources, may be at a higher risk during heat waves, especially if they do not have means to cool down,” the assessment states.

The worst impacts of extreme heat have already caused deaths in other states, with disproportionately high death rates reported among people experiencing homelessness. Of 339 people who died of heat-related illness during a 2021 heat wave in Phoenix, 130 were homeless, according to a report published by Maricopa County officials.

In Oregon, a state not known for hot weather, at least 115 people died in a 2021 heat wave, though little data exists about how many of those people were unhoused.

“There was just a really substantial amount of health impact, and unfortunately, fatalities there,” said Jared Ulmer, climate and health program manager at the Vermont Department of Health. “We haven’t quite hit that point of extreme heat here. That’s what we want to really be prepared for.”

Ulmer said his program received a grant from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2012 to analyze potential impacts of climate change and work to find solutions. He and his colleagues have spent much of that time focused on how to keep people safe in the heat.

“That’s one of the most immediate areas where we’re going to feel impacts,” he said. “And, frankly, we’re pretty underprepared for a really extreme heat event in Vermont.”

Barriers to access

According to Sarah Phillips, who works at the Agency of Human Services as the director of the state’s Office of Economic Opportunity, the state’s strategy around heat and homelessness has several prongs. One comes in the form of pre-pandemic funding to support community-based day shelters and keep them open during all types of weather. More seasonal shelters are typically open in the winter, she said.

“These are shelters that only operate during the cold weather months. And I think that will continue to be a part of our continuum of care, is thinking about what kind of seasonal capacity we need,” Phillips said. For example, the state could consider expanding capacity in the summer.

Another prong, and the only strategy that’s directly related to the end of the motel program, is a request from the Department for Children and Families for leaders of municipalities, emergency shelters and other entities to submit requests for funding and aid to alleviate problems related to homelessness.

Municipalities have submitted a wide range of requests, Phillips said. She expects that the state will be able to distribute some aid in time for a portion of the projects to be completed this summer.

“Some folks have the staffing, they just need some funding to expand hours, for instance,” she said. “Or some folks have identified a site, but they might need some staffing support. So there’s a huge range.”

The state strategy referred to most often is a map of public cooling locations, open to everyone, such as libraries and state parks. It’s issued by the Department of Health, which is housed within the Agency of Human Services. The map shows 270 entries, statewide, but some aren’t as useful for people who don’t have shelter.

Advocates and people who are experiencing homelessness say that this patchwork of available shelters and public cooling locations is tricky to navigate and sometimes difficult to access, due to, for example, a lack of public transportation.

Of the 270 entries, 144 listed cooling locations are recreation sites with water access, which is not an ideal option for people who don’t have shelter — and half charge a fee for use.

“If you’re experiencing homelessness and you’re carrying around all your bags and all your gear, I wouldn’t say that (Lake Champlain) is readily accessible,” said Paul Dragon, executive director of the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity.

While libraries, particularly the Fletcher Free Library in Burlington, have been “really wonderful in hosting people,” people don’t always have transportation to get there, Dragon said. “We have to remember that not everywhere in Vermont has the centralized infrastructure, either, that Burlington has.”

Another 94 locations on the state’s map are listed as public facilities “with cooling.” But advocates have questioned whether those public facilities are truly accessible to people experiencing homelessness.

Bob Joly, director of the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum, was surprised to hear the library and research nonprofit was listed as a cooling location. Only its art collection is kept cold.

“The art is happy, but the whole rest of the building has no climate control,” he said. He struggled to think of another spot in St. Johnsbury that could function as a cooling location.

In Montpelier, the department’s map includes the Statehouse, the senior center, the police department, the Capital Region Visitor’s Center and the Kellogg-Hubbard Library.

Ken Russell, director of Montpelier-based Another Way, a community center for people experiencing homelessness and psychiatric survivors, said many of the capital city’s cooling locations are “not welcoming places for this population,” and many have varying hours that are often reduced on the weekend.

A regional team working on the issue looked into buying passes for state campgrounds, Russell said, but found they were largely too remote for people who need to access cities for opportunities and services. He hoped the state would consider loosening its policy on camping on state land in non-designated areas, as Montpelier did when the city decriminalized camping in Hubbard Park.

People seeking cool shelter sometimes find their way to Another Way’s porch on Barre Street, said Russell. He recalled one hot day where the organization hosted a barbecue, and he grew worried for a man with disabilities who was “laying out” in the heat.

“We did our best to sort of wake him up and make sure he was in the shade and give him some water,” Russell said.

Russell is worried that, as the motel program scales back, “the gap between what’s needed and what’s available is about to get much wider.” Vulnerable people are living out in the elements because so few shelter beds are available.

“We’re about to face catastrophe,” he told VTDigger in May, when the motel program appeared to be soon ending entirely and before lawmakers reached a deal that would keep thousands sheltered longer. “The mortality rates are already — and I hate talking about this as statistics — but people are dying already. It’s just disturbing how many people are dying.”

Navigating the heat

In fall 2022 and spring 2023, Middlebury College students worked with the Vermont Department of Health on a project that sought to understand the impacts of heat on people experiencing homelessness.

Students conducted anonymous surveys of people staying in shelters. The responses told stories of strife, sometimes dire:

“When passed out in a parking lot, people thought I was sleeping.”

“My vision went white and (I) almost fainted from heat exhaustion. It was most likely due to little water access.”

“Not everyone wants a homeless person sitting around just to cool off.”

The level of a person’s vulnerability, the resulting reports noted, can depend on whether a diagnosed mental illness might require medications, such as antipsychotics, that make it difficult for the body to thermoregulate. Nearly three-quarters of respondents reported having a diagnosed mental health condition.

The report found that a lack of health care exacerbated the impacts of heat-related illness among the homeless population. Researchers acknowledged that underlying problems in the medical system need fixing, but said the situation could be significantly improved by distributing first aid kits that include “ice packs, water, iodine tablets, electrolyte tablets, Narcan, and basic first aid equipment such as antibiotic ointment and gauze.”

Ulmer, with the Department of Health, sees a range of long-term solutions helping to keep unsheltered Vermonters safe during the heat: affordable housing; building weatherization; more temporary shelter space; and ensuring that supplies, such as clean water and battery-powered fans, are available.

Asked whether the state has enough resources to begin working on those solutions, Ulmer said he couldn’t say.

“My understanding is, everybody’s doing as best they can with the resources available,” he said.

Box stores and windy spots

Maughan, the advocate for vulnerable populations in Vermont, is better able to manage the heat in his converted van, he said, where he has running water and can change in his own space.

“I just tried to find windy spots and shade to park,” he said. “Which also means you have to keep moving around.”

But he’s also felt the impacts of the heat.

He performs contracting work outdoors, and said he expects to experience heat exhaustion several times per year. Even when he came home to an air-conditioned motel room in May, he said, he vomited “profusely” after pushing himself hard at work.

“You basically just have to stand in front of an air conditioner until you’re OK to move,” he said. And that’s not an easy feat for those who live outdoors.

Instead of a library or a day shelter, he recommends that people who need to cool off go to big box stores, which usually have air conditioning, to walk around.

“As long as you continue moving, businesses aren’t really that suspicious. It’s when you bring in a bunch of backpacks, and you’re hanging out in one corner for a while, that they’re like, ‘Hmm, I don’t know,’” he said.

Maughan wants to see more communication from public officials about where people who don’t have shelter can park, and can stay and rest outside, without being asked to leave. He also said more information needs to be available about indoor cooling locations.

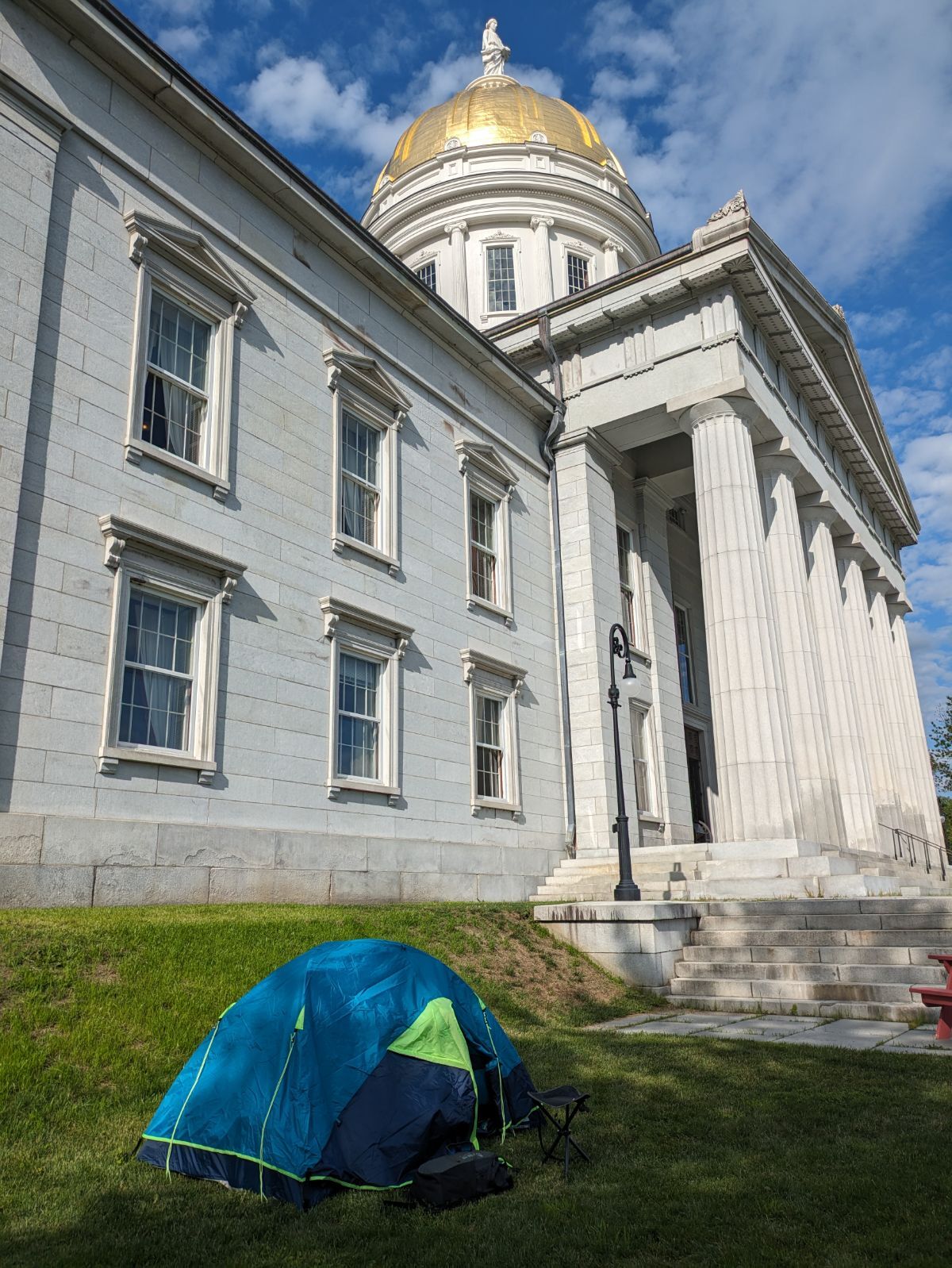

He pitched a permitted tent last week in front of the Statehouse as a message to lawmakers who had been debating whether to extend the motel program. In interviews, he often expressed concern about others who might have more challenging conditions than his.

While Maughan’s throat was hurting from the smoke, he worried about others who are elderly or have respiratory issues and faced the same level of exposure.

His van setup has made him more comfortable and self-sufficient, and sometimes helps him stay cool. But he wondered how others, living in encampments, would fare. They’d need to leave their belongings behind to seek cool daytime shelter, risking that they might be stolen, or stay in one place and endure the heat.

“I don’t know how they’re gonna stay cool,” he said.